Saucer People (Part 1): Three Minutes Over Mount Rainier

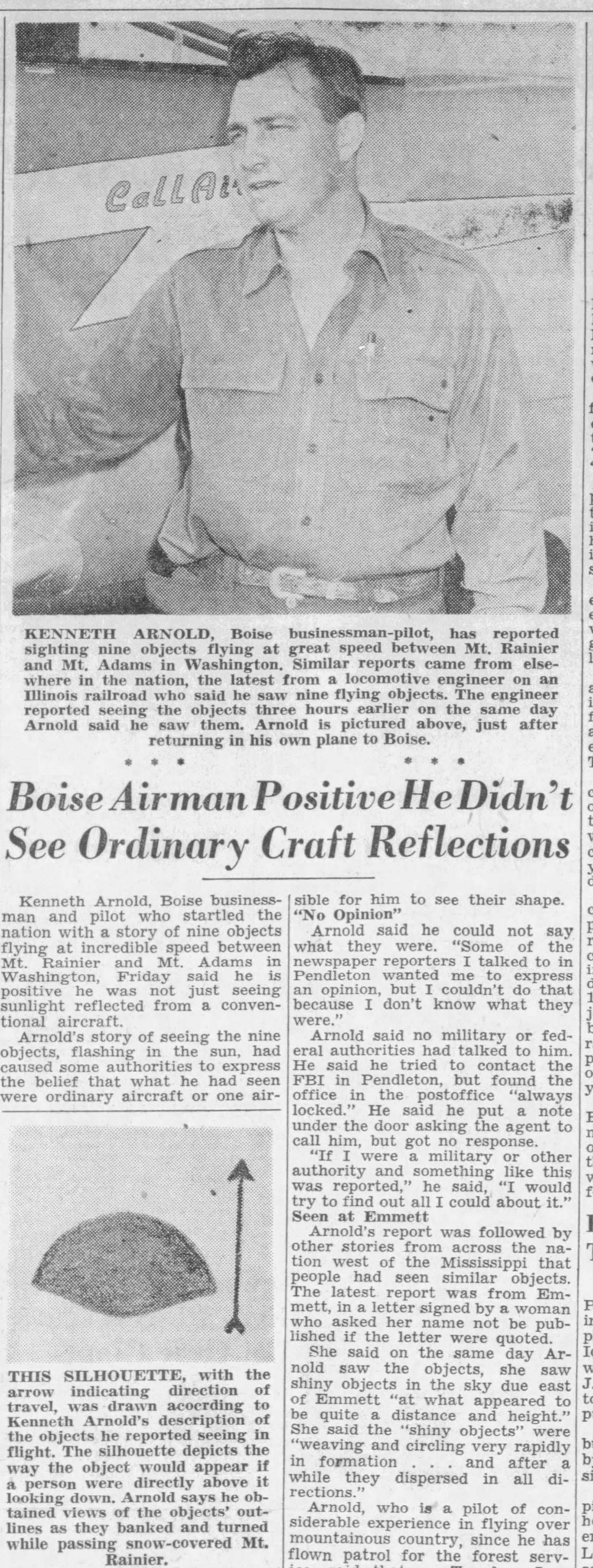

In June 1947, Kenneth Arnold, a businessman and pilot from Boise, Idaho, triggered the modern UFO craze after reporting mysterious objects he allegedly witnessed in the skies over Washington state

This is the first in a series of stories about important alleged early encounters with UFOs – or, as they were called at the time, “flying saucers” – and the men and women who helped kick off the modern UFO craze. I’ve done extensive research for a cultural history of flying saucers (which later became known as UFOs) in Postwar America. I thought that instead of writing a book about the topic, as I had initially planned, it might be fun to share these stories with you on Substack. I’ll post them regularly. I may post other items in between these stories, but my goal is to write what would’ve been my flying saucer book in its entirety here on Substack. But the wonderful thing about Substack is that I can lean more heavily into the storytelling and make it more fun, less academic. Anyway, my friends, this is a story about Kenneth Arnold (1915-1984), a businessman from Boise, who claimed he witnessed multiple flying objects over Mount Rainier in June of 1947, which ushered in the modern UFO craze. His story went viral in a huge way, decades before the coming of the internet. Other “Saucer People” stories will be published here regularly in the future.

Enjoy!

Three minutes. Or a hundred and eighty seconds, if you prefer. That’s how long it took to change Kenneth Arnold’s life when the incident happened on June 24, 1947. Three minutes. And it changed everything for him. Forever.

Think about it. Three minutes. It takes longer to prepare instant rice (which, by the way, was introduced two years later, in 1949, by General Foods).

Three minutes. Nine objects flew through the sky at high speeds. Arnold guesstimated they were moving at roughly between 1200 and 1600 miles per hour – depending on which interview with him you read or heard. Faster than any conventional aircraft could fly.

Three minutes. On that life-changing day – a Tuesday, around 2 p.m. – businessman Kenneth Arnold was flying his small CallAir A-2 aircraft. He’d taken off from Chehalis, Washington, and was heading to Yakima, in the same state.

Arnold was in Washington conducting business. Between meetings, he picked up a local newspaper and read about a search for a downed Marine C-46 transport plane. The article mentioned a $10,000 reward.

Arnold climbed into his airplane and took off, to see what he could see.

Three minutes. Kenneth Arnold was 32 years old at the time. He’d live another 37 more years, dying of colon cancer in 1984 at age 68. For the rest of his life, those three minutes would define his life, and his legacy.

The objects came seemingly out of nowhere, ten thousand feet above the southwest side of Mount Rainier. All nine of the objects appeared big. Arnold guessed each one to be about the size of a DC-4 aircraft. A DC-4 was no puddle-jumper. A big four-engine airplane, it could hold a couple of dozen passengers. They were used as transport planes during World War II. After the war, the big airline companies bought them all up: Pan-Am, Northwest, Air France, Scandinavian Airlines, Swissair, KLM Royal Dutch – and plenty of others.

So these were immense objects that Arnold spotted. And they flew faster than any conventional aircraft known at the time could travel. They were, according to Arnold, metallic, crescent-shaped, flying in formation. They appeared to be about 30 miles away when Arnold saw them. The objects soared southward over Mount Rainier. Arnold watched them until they faded into tiny specks, and eventually, out of sight.

Above: Edward R. Murrow interviews Kenneth Arnold for CBS Radio, April 7, 1950, who offers a vivid description of the objects he sighted over Mount Rainier, Washington, almost three years earlier.

Arnold landed at Yakima airport. He told his friend, Al Baxter, general manager of the facility, what he’d just witnessed. Arnold recalled that Baxter reacted with skepticism. Moments later, Arnold returned to his plane, took off, and flew to Pendleton, Oregon. While in Pendleton, the day after the sighting – June 25 – Arnold made his way over to the local newspaper, the East Oregonian. He asked to see a reporter. He told the reporter about the objects.

The East Oregonian immediately ran a story about Arnold’s mysterious aerial encounter. The story went out on the Associated Press (AP) wire service across the country. The lead in the article said: “Nine bright, saucer-like objects flying at ‘incredible’ speed at 10,000-feet altitude were reported here Wednesday by Kenneth Arnold, a Boise, Idaho, pilot, who said he could not hazard a guess as to what they were.”

The day after the sighting was reported, an official with the Civil Aeronautics Administration (or the CAA) told reporters: “If they were actually as described, I don’t know what they could be. I rather doubt that anything would be traveling that fast.”

Newspapers across the country – in big cities and small towns alike – widely reprinted Arnold’s account. Upon returning to Boise, Arnold felt overwhelmed by the thousands of letters and telegrams he received. Back at the Great Western Fire Control Supply, the company that Arnold owned, the telephone was ringing off the hook with requests for interviews.

Before the end of July 1947, Arnold had been bombarded with invitations from across the country to speak, offers from publishers to write about his experience, and urgent pleas from producers of radio programs to come on the air as guest on popular talk shows of the day.

A significant part of Arnold’s appeal was his reliability. Why would someone held in such high regard, so modest and sensible – someone who was clearly not an attention seeker – make up a story like this? Historian Mike Dash astutely observed: “Arnold had the makings of a reliable witness. He was a respected businessman and experienced pilot . . . and seemed to be neither exaggerating what he had seen, nor adding sensational details to his report. He also gave the impression of being a careful observer.... These details impressed the newspapermen who interviewed him and lent credibility to his report.”

Dash was right. People trusted Kenneth Arnold. They found him convincing and reliable. But the man had his detractors, too. Days after the incident, Arnold told an Associated Press reporter: “Everyone says I’m nuts. And I guess I’d say it too if someone else reported those things. But I saw them and watched them closely. It seems impossible, but there it is.”

In its January 1951 issue, Cosmopolitan magazine featured a story headlined, “THE DISGRACEFUL FLYING SAUCER HOAX,” which criticized Arnold for “igniting a chain reaction of mass hypnotism and fraud.”

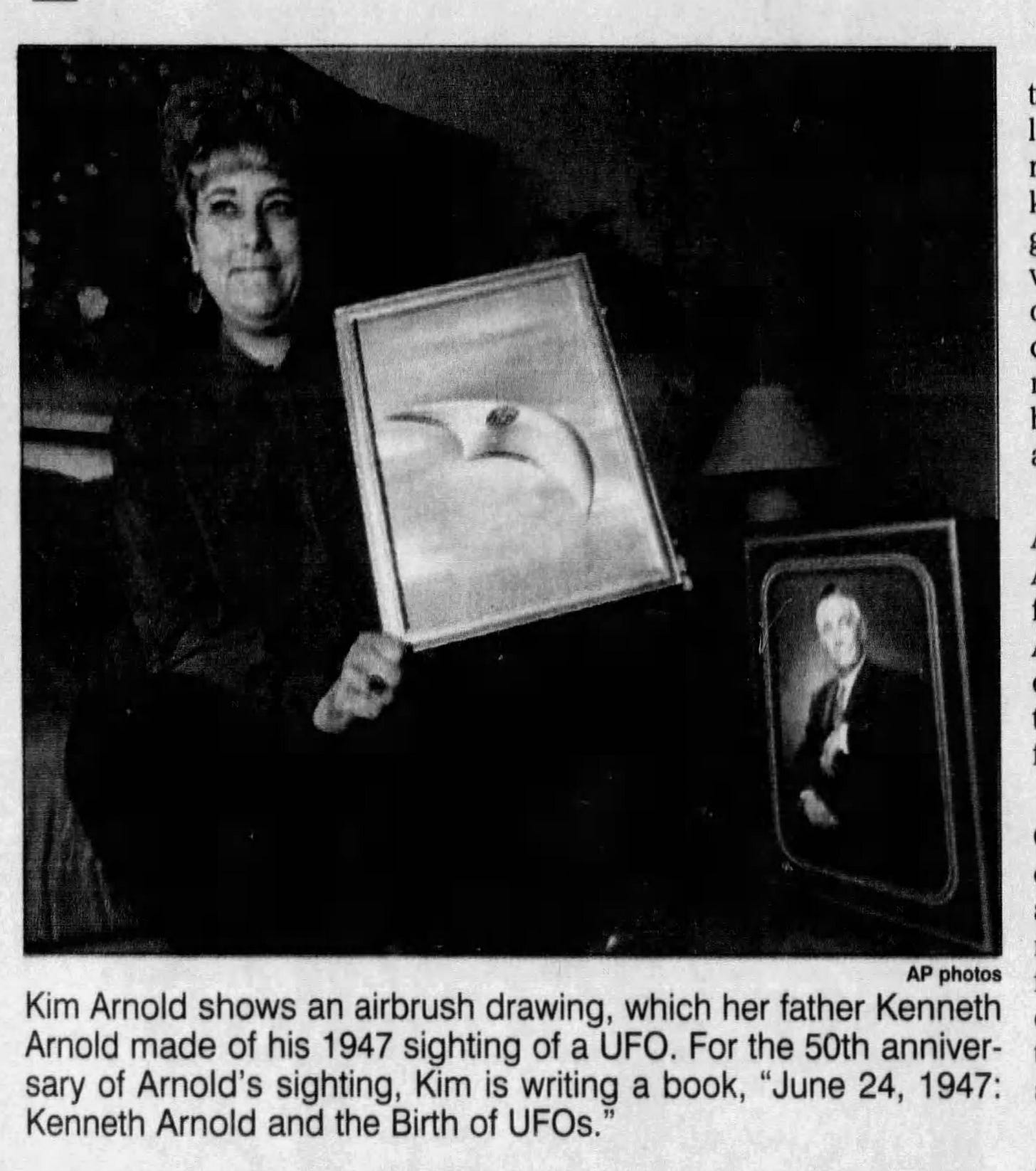

Arnold’s sighting touched off the modern Unidentified Flying Object (or UFO) craze of the Postwar Era. After the incident, Arnold famously likened the objects he saw to “a saucer if you skip it across the water.” In other interviews, Arnold said they were “flat like a pie pan,” and “saucer shaped.” After that, the term “Flying Saucers” stuck. For years, it was used interchangeably with UFOs.

Three minutes. That moment was all it took to catapult Kenneth Arnold to fame. His name forever became associated with UFOs. In the weeks, months, and years after Arnold walked into that newspaper in Pendleton, Oregon, untold numbers of eyewitnesses reported sightings of mysterious objects in the sky.

And not just above the United States. This Golden Age of UFO sightings exploded into a worldwide phenomenon. The mania reached a fever pitch in North America with the 1952 Washington, D.C. UFO incident, which was really a series of sightings of strange glowing objects over the nation’s capital.

Objects seen in the skies assumed a variety of shapes and sizes: There were oval objects and round objects. There were cigar-shaped objects, and there were disc-shaped objects, some with domes, some without. There were silvery or metallic objects, some of which reflected light. And there were bright lights. Sometimes there were multiple lights, and they flew in formation. There were objects that hovered low. Objects that landed. In 1961, fourteen years after Kenneth Arnold’s encounter, an interracial couple named Betty and Barney Hill revealed under hypnosis that they had been abducted by aliens in a UFO along a lonely stretch of rural highway in New Hampshire.

For a time, Arnold immersed himself in the UFO controversy. He became a spokesperson, of sorts, for the waves of flying saucer encounters that followed his own – a human face for flying saucer mania. Decades later, Arnold’s daughter, Kim, recalled: “Anyone who had any kind of UFO or paranormal experience showed up on our doorstep. They came from everywhere, and it just kept growing. LOOK magazine did a big story on my dad. One of the networks flew him to New York to be on What’s My Line?. He received over 10,000 letters.”

In 1952, Arnold’s book The Coming of the Saucers appeared in bookstores across North America and climbed high on the bestseller list. Arnold went on to become one of the founders of an organization that investigated UFO sightings.

But the pressure and tension that came with fame took a toll on the family. Kim Arnold said that one of her sisters was so troubled by the barrage of media attention that she refused to talk about her father, or his alleged UFO sighting. As she later explained: “Having a father who became famous over one of the most controversial issues of the century was hard on all of us. You know the family in Close Encounters? We were that family, 30 years earlier.”

Being pulled into the middle of the vortex of the UFO craze took a toll on Kenneth Arnold’s physical and mental health. With the passage of time, as more people began to voice doubts about his claims, he grew increasingly embittered. By the 1950s and 1960s, the U.S. government – in particular, the Air Force – had launched multiple campaigns to discredit reported UFO sightings. The names of the different efforts changed over time – Project Grudge, Project Sign, Project Bluebook, the Condon Report, the Robertson Panel – but the end goal was always the same.

Debunk. Plant doubts. Marginalize eyewitnesses. Find rational explanations to dismiss alleged UFO sightings.

They saw birds. Or weather balloons. Or swamp gas. Or aircraft. Or unusual cloud formations. Or stars. Or shooting stars. Or whirlpools of air. Or planets (the planet Saturn was the one most often implicated).

And there were also mirages. Electrical plasma effects. Fireworks. Lightning. Experimental military aircraft, such as the Vought V-173, a flat, disc-like twin-propeller airplane also known as the “Flying Flapack.” And Natural Light Displays (such as aurora borealis). According to the experts, all these things were distorted by a mix of fog, mist, temperature inversions, sunlight, moonlight, and ice crystals in the atmosphere.

Debunkers in government and the armed forces took part in a systematic crusade – spanning decades – to convince people that UFOs were not alien spacecraft. And their efforts proved at least partially successful. While most opinion polls indicated that a sizable number of Americans believed that Unidentified Flying Objects were piloted by extraterrestrial visitors from distant planets, an even greater percentage of people expressed doubts that aliens were indeed visiting earth.

So, what did Kenneth Arnold actually see in the skies above Mount Rainier? Optical illusions? Experimental aircraft? Maybe he was lying? Or . . . Did he happen to witness flying saucers from a distant planet?

We will never know the answer to that question.

But what we do know is that those three minutes – thousands of feet high, in the blue sky – defined Kenneth Arnold’s existence for the remainder of his life. And after.

The rest of his life remains largely forgotten:

That he was a Boy Scout in his youth, known for his love of nature (in particular, he developed a passion for studying birds).

Or that he took his first airplane ride in 1929, at age 14, over Great Falls, Montana, and his first flying lesson two years later. Or that he was the star of his high school football team, and he exhibited great talent on the gridiron while a student at the University of Minnesota.

Or that his first automobile was a Model T, and he sold sportswear before he sold fire extinguishers. Or that he flew Mercy Flights for Idaho Search and Rescue, a humanitarian organization that flew missions to save people in mountainous terrain.

Or that he married his wife Doris, and they started a family, and had four daughters. Or that he ran for Lieutenant Governor as a Republican in the 1962. Or that, as he got older in the 1970s and 1980s, he became increasingly angered about his integrity being questioned in certain press accounts of his 1947 sighting. Or that this business continued to thrive for the rest of his life. Or that he died of cancer on January 16, 1984, at only 68 years of age, known mainly for those three minutes – that life-altering 180 seconds – over the Cascade Mountains, 37 years earlier.

It’s worth letting Kenneth Arnold have the last word here, in this excerpt from his 1952 book The Coming of the Saucers:

“What I saw over the Cascades in the State of Washington, as impossible as it may seem, is fact. I never asked, wanted, nor expected any notoriety for accidentally being in the right spot at the right time to observe that chain of nine mysterious objects.”

Well written. I've never followed the UFO phenom, and count myself a skeptic, but look forward to changing my mind. More interesting than what did he see is the craze it started. We really want to believe there's other life forms in the universe.

I think the Trump congress wants to re-open the UFO controversy